Phillips Farm — So Historic, They Want To Capitalize on It

Geraldine BrooksAugust 24, 2003

Waterford, Va.

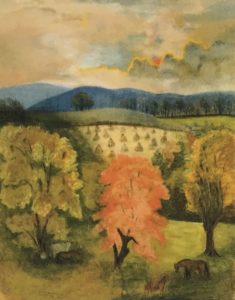

In the waning summer of 1899, a Quaker woman named Mary Dutton Steer made a pastel drawing of the view from her back window. It depicted the Phillips Farm, the very first piece of land that Quakers from Pennsylvania had chosen when they came south to Virginia and settled here in Waterford in 1733.

In the waning summer of 1899, a Quaker woman named Mary Dutton Steer made a pastel drawing of the view from her back window. It depicted the Phillips Farm, the very first piece of land that Quakers from Pennsylvania had chosen when they came south to Virginia and settled here in Waterford in 1733.

The farm she drew remains beautiful at all times of the year: in winter, when the snowy fields are tessellated by the tracks of wild geese; in spring, when the trees unfurl their first fresh green; in summer, when the heavy air lays a blue haze on the rising hills and mist hangs over the creek, milky as white opal. But Steer was an artist, and so her eye sought the loveliest time of all -- when the farmland's promise is fulfilled in rows of fat golden haystacks and the first locust tree has begun its blushing acknowledgment of fall.

I know this, because I live in Steer's house now. The farmland she depicted has remained essentially unchanged for more than the century that stands between us. I have seen 10 summers wax and wane here, and have felt connected to the Quakers who toiled to clear that land, to the common soldiers of the Civil War who bled upon it, and to the modern-day tenant farmer whose cows have grazed it through these recent years of drought and hardship.

Late last winter, the Washington family who own the Phillips Farm sold 144 acres of it -- the fields and ridgeline, the woods and creek with the old stone Quaker dam that provided water for the town's first grist mill -- to a developer who immediately submitted plans to cover the land with 14 luxury houses. The farmer has had to move his cows. The fields have stood silent and empty all summer, and this fall there will be no hay made. The buyer, whose identity is shielded under Virginia corporate law, calls itself Historic Fields LLC -- a bleak joke, given that there would be no historic fields once its proposed subdivision is built. The only name associated with Historic Fields is the signature on the line of credit used to pay the $2.2 million purchase price, that of one David Dobson, a Harvard- and Yale-educated lawyer who practices in Rome.

The sale shocked Waterford, a small community, home to only 80 families, that had been in negotiations with the family to buy the land through our nonprofit preservation organization, the Waterford Foundation. The foundation had tried to make it plain that it would better the developer's offer. We don't know, and probably never will know, why the family acted as it did. But within three hours of the land changing hands last March, the Waterford Foundation offered Historic Fields $2.5 million to buy and preserve it. Paul MacMahon, the Middleburg real estate agent acting for the developer, dismissed that offer -- a profit of a mere $100,000 an hour -- and told the foundation to come back when it had $3.9 million.

History is being held ransom here. The past this village represents -- not the past of great deeds and grandeur, but the past of humble, hardworking rural America -- was honored in 1970 by the Department of the Interior, which named Waterford and its surrounding farmland a National Historic Landmark, placing it on a par with the likes of Mount Vernon and Independence Hall.

And yet this designation offers no protection. It is, in the end, only that: a design, an intention to honor the past. But the past isn't honored by faceless developers demanding almost double what they paid. If the foundation can't find the money by an Oct. 31 deadline, then most likely, the farmland that cradles the village will be entirely gone by next year, buried under million-dollar mansions that would dwarf the modest old Quaker homes and almost certainly mean the loss of the village's historic landmark status.

Property rights advocates would say, so what? People need housing, and there's nothing wrong with making a profit. But souls have needs, too, and sometimes the lust for profits can be spiritually bankrupting. Those property rights advocates would say that when I bought the Steer house, I made it mine, to do with what I please. But I don't see it that way.

Even if I live out the rest of my days here, it will be only a short episode in the history of a house that first sheltered a family in 1815. Therefore I don't think that my rights, here and now, transcend those of the people who came before and will come after me. I don't think I have the right to obliterate the traces of the house's past that linger within it: the trapdoor in the ceiling through which the children of the Steer family were hoisted nightly on their parents' shoulders to sleep -- in those pre-central heating times -- in the cookstove-warmed kitchen loft; the marks of the hand-forged nails in the oak beams or the errant coal that singed the wide pine floors.

Just before I moved here, the previous owner unearthed a Union soldier's belt buckle that had lain buried near the stone-lined well from which the Steer family drew its water. When I hold it, I am transported to a time when Waterford's Quakers faced an agonizing test of conscience. Ardent in their abolitionism and equally ardent in their pacifism, some found slavery an evil worse even than war and were among the few Virginians who took up arms on the Union side. Because of that buckle, and the questions it seeded in my imagination about the young man who wore it, I am writing a novel now about a pacifist at war. But I'm not the only one to feel the tug of that small object. Every October, when 30,000 visitors come here for Waterford's house tour and craft fair, I show the buckle to the schoolchildren who troop through my house, and the wonder in their faces tells me that they, too, are transported and connected to this young man from our past.

It won't be easy to raise the funds to save Phillips Farm. Those of us who live here and enjoy the daily blessing of this place will give as much as we can. But we are few, and some of Waterford's residents are minimum-wage workers and some are elderly and on fixed incomes. The village has received support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Farm and Ranchlands Protection Program, which will give us $800,000 if we can match it. There is also a preservation grant from the federal Transportation Enhancement Program. That still leaves $1.7 million that we must raise to provide the price that Historic Fields demands. If we succeed, the land will remain a working farm, as it has been for 270 years, but with access for the public to enjoy it.

We owe it to the people of this increasingly urbanized region, who come here all year, by bike or on foot, to enjoy the free tours the foundation's volunteers offer and to draw replenishment from a beautiful landscape with a rich history. We owe it to the thousands of schoolchildren who take part every year in the village's unique Second Street School program, experiencing a day in the life of a 19th-century African American pupil attending the town's one-room schoolhouse.

But we also owe it to the people who settled the farms and built the simple houses -- to people like Mary Dutton Steer, who were inspired by this place. They were mindful people, who valued the land for more than profit, and kept it, so that we in our turn might keep it safe as an enduring inspiration for future generations.