Loudoun's Transportation Congestion

Traffic up 30-60% since 2001

Loudoun Times-Mirror

September 27. 2006

By Anne Keisma n

Kristen Thatcher drives from her home in Hillsboro to Washington, D.C., five days a week for her telecommunications job. The commute takes her about two hours each way. At 5:50 a.m., Hillsboro resident Kristen Thatcher gets into her black Saturn and points it toward her job at a telecommunications firm in Washington, D.C.

A few moments later, on Route 9, she's already stuck in traffic. Commuters jam the only road connecting the less pricey homes in West Virginia with metro-area job centers. Two hours later, Thatcher arrives at her office in Northwest D.C.

"We are getting to a point where things are really dire," she said, referring to Northern Virginia's road network "We are heading toward a crisis."

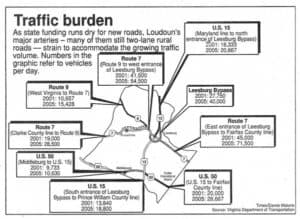

The crisis is already here, according to state statistics. Route 9 has had to accommodate 50 percent more cars since 2001. In 2005, the two-lane rural road handled an average of 15,428 vehicles a day, up from 10,657.

Kevin Reed, a teacher at Frances Hazel Reid Elementary School in Leesburg, coaches girls' basketball at Loudoun County High School - also in Leesburg. His drive from his home in Stevens City, south of Winchester, can take 80 minutes.

"My wife calls herself a basketball widow," said Reed, adding later, "It's unfortunate I can't live where I work or work where I live."

Lack of affordable housing and a failing transportation network remain the twin political dilemmas in Northern Virginia. Loudoun, as the region's fastest-growing county, is the lightning rod for the debate.

This week, in Richmond, many miles from Thatcher and Reed's daily realities, legislators in the state's General Assembly have reconvened to come up with a solution for the second problem: transportation funding.

So far, prospects look dim. A bill to raise $400 million a year for regional road improvements through taxes and fees levied in Northern Virginia died Tuesday in the House of Delegates' powerful Finance Committee.

"It's really disappointing, but not entirely unexpected," said Del. Joe May (R-western Loudoun), who supported the bill as a way to keep tax revenues in Northern Virginia, and not have them siphoned off to the rest of the state.

The plan, devised by Dels. Tom Rust (R-Loudoun) and Dave Albo (R-Fairfax), would have included impact fees on developers and increased commercial real estate tax. The region's business community, including the Loudoun County Chamber of Commerce, had supported it wholeheartedly, even though it would have been hit the hardest.

May said he felt confident that some compromise could be made to get money for Loudoun roads.

"This is only the first round," he said.

The Virginia Department of Transportation provides statistics that foresee a frightening future: By 2025, there will be no more funding for road construction in the state. It will all be needed to maintain the roads we've got.

Also, the cost of the materials and real estate needed to build roads continues to skyrocket. In a recent 18-month period, the cost of road right of way for the I-66/Route 29 interchange increased by $40 million.

The region will face economic problems if the issue isn't addressed, said John McClain, deputy director of the Center for Regional Analysis at the George Mason School of Public Policy.

"It is becoming harder [for businesses] to recruit people," McClain said. "People have to make extreme adaptations - getting up at 5 a.m. to drive to work. After awhile, they might get fed up and find a job somewhere else."

For now, though, the job-growth forecast is astounding. In the metro region, an average of 64,000 new jobs a year is anticipated until 2010, according to the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

A 200-percent increase in jobs within Loudoun's borders is forecast by 2030. But D.C. and the inner suburbs will still reign as the top employment center with one-third of the regional jobs -- which means more commuting for Loudouners.

Broad Run Supervisor Lori Waters (R), contacted last week while she was driving Loudoun's roads, said she didn't support the tax increases. Her constituents already pay plenty to the state, she said, in addition to all the other costs associated with driving.

"I just filled up my car with gas and paid the toll for the Greenway," she said. "Commuters are already paying so much." Reallocating existing resources is the key, she said. Recent statistics show Northern Virginia gets about 20 cents back for every dollar sent to Richmond.

In November, voters will get to decide whether they want to pay for roads in yet another way: real estate taxes. A bond referendum, if approved, would authorize the Board of Supervisors to use local taxes to tackle some the county's worst traffic snarls - road improvements that are so far down on the state's priority list, they risk never being funded.

Waters does support this use of tax dollars. "I do think we should have a piece of the pie devoted to roads," Waters said. "It's really a public safety issue."

In her district, she said, two-lane Route 659 is especially dangerous, carrying more than 15,000 vehicles daily between Route 7 and the Greenway. That's up from about 6,000 a day in 2001.

But, as Richmond and local officials fight the familiar tax-and-spend battle, another group is proposing a transportation solution: developers.

Outside of Loudoun's recent public hearings on future development along the U.S. 50 corridor, developer employees displayed colorful maps, posters and fliers, touting their most enticing bargaining chip: the road proffer.

If local government approves more residential development, it gets the chance of negotiating millions of dollars worth of road improvements with the developer.

The message: The state has failed. It's time for the private sector to step up to the plate.

The Dulles South Transportation Alliance, a group of landowners and developers with projects pending in that rapidly growing part of Loudoun, met biweekly for 18 months to cobble together $750 million in road improvements for this area, amounting to 200 miles of new lane miles.

The group includes Greenvest, which has 15,000 homes proposed north and south of U.S. 50, Buchanan Partners, which wants to build a town center with 1,300 homes near Arcola, and other developers with projects in the area.

"This is an unprecedented, coordinated effort -- certainly on this scale," said Tony Calabrese, spokesman for DSTA. "It's a perfect storm of need and committed resources."

Critics point out a seeming contradiction: Wouldn't allowing more homes just lead to more traffic?

Calabrese says the capacity of the roads planned would accommodate far more than what the development would generate. Also, he adds, job growth is really the driving force. If there aren't homes in Loudoun, people will leapfrog over the county to West Virginia or Winchester - and use Loudoun's roads anyway to get to work.

"That's a convenient developer-fib," said Bob Lazaro, spokesman for the Piedmont Environmental Council, who opposes the development proposals in Dulles South.

He added: "Does anyone in Loudoun County really think that building all those houses is going to help traffic?"

While proposals and counter-proposals swirl, one thing is certain: Commuters like Reed and Thatcher spend more and more time in their cars as routes 7, 9, 15 and 50 continue to resemble parking lots.